Cognitive Screening Tools

Primary care plays a central role in the early detection of cognitive impairment, offering opportunities to address reversible causes and support brain health. Early assessment can improve outcomes by slowing progression to Alzheimer’s and related dementias, reducing risks, and improving quality of life. Despite known benefits, barriers to cognitive testing in primary care still limit widespread implementation. However, advances in tools, biomarkers, and clinician resources now make early detection more practical and valuable, highlighting the need to integrate these strategies into routine care.

Initial Clinical Assessment and Mental Status Evaluation in Primary Care

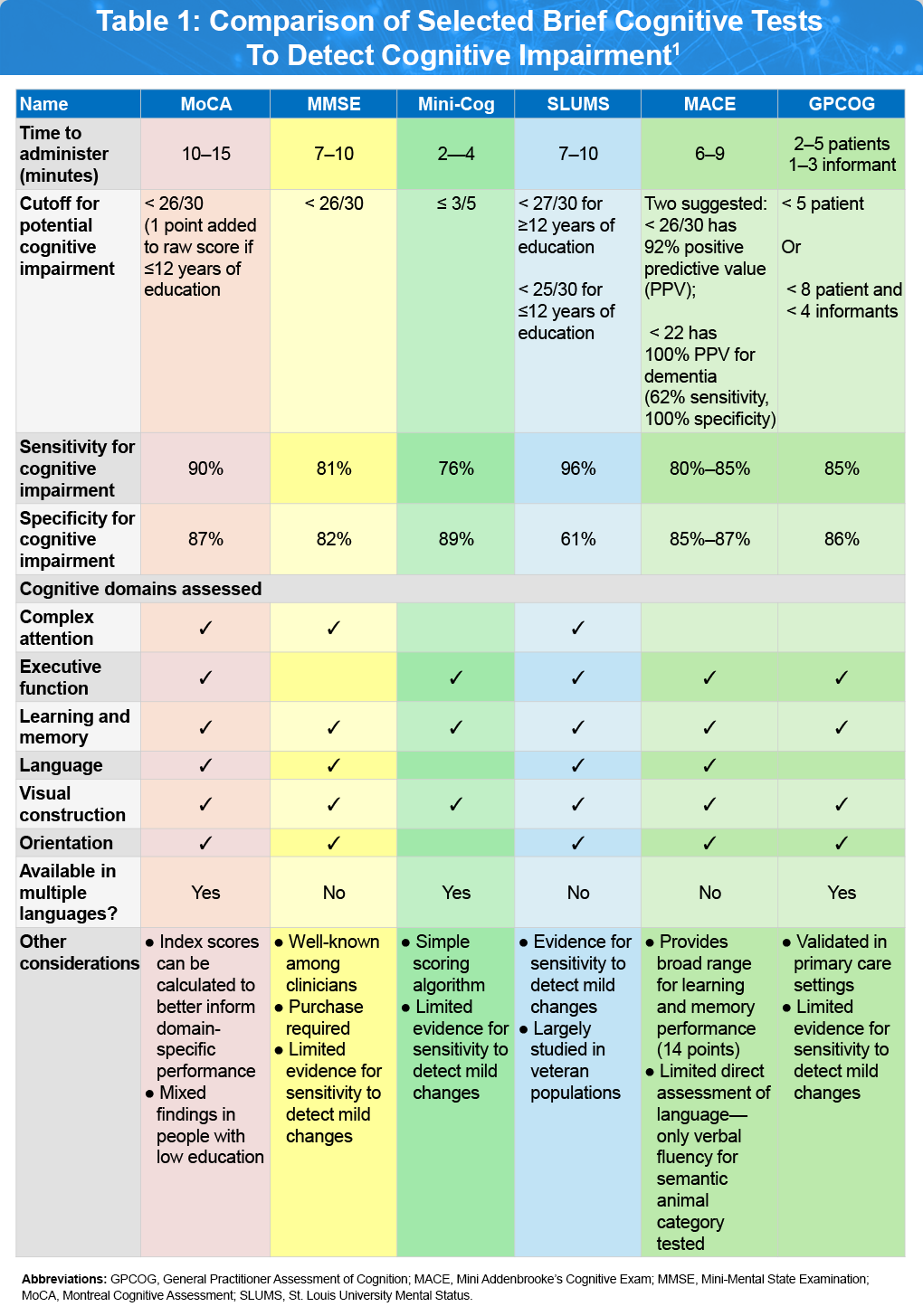

Regardless of whether the patient or a family member initiates the medical visit, the initial focus should be on obtaining a thorough description of the patient’s primary cognitive and behavioral symptoms, including their impact on daily functioning, relationships, and behavior. This should also include the timeline of symptom development, the presence and progression of other relevant symptoms, and pertinent medical history and risk factors. Through this interaction, a primary care clinician may recognize clear changes in the patient’s cognition, mood, or behavior compared to their baseline, prompting the need for a formal mental status examination. A first-tier assessment of cognitive function, mood, and behavior can typically be conducted efficiently during a problem-focused primary care visit, with several tool options available, each with its own advantages and limitations, as outlined in Table 1.1

Selected Brief Cognitive Tests

Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)1,2

The MoCA is a widely used cognitive screening tool designed to detect mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and early Alzheimer’s disease. The MoCA generates a total score of 30 points for items categorized into six domains: memory, executive functioning, attention, language, visuospatial, and orientation. This test is especially valued for its utility in identifying relative impairments in specific cognitive domains, which can assist with clinical diagnosis and phenotypic characterization and can be particularly useful in primary care settings in which brief screening instruments are favored. MoCA is available in multiple languages and various options exist for remote administration with further validation for specific cut-offs and potential age- and education-adjustments. Click here to access the MoCA assessment tool.

Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)3

The MMSE is a brief cognitive screening tool that offers a general assessment of cognitive function. In patients with MCI, it is often complemented by more detailed neuropsychological tests targeting areas like language, praxis, and executive functioning. Its strengths include ease of use, minimal resource requirements, no associated risk, and high acceptance among healthcare providers managing dementia. While the MMSE is commonly used in clinical practice for initial evaluation of MCI, clinicians should be aware of its limitations in predicting progression to dementia, especially when more comprehensive testing is not accessible. Another major limitation of the MMSE is that it is now the subject of copyright issues.

Mini-Cog4

The Mini-Cog is a very brief cognitive screening tool shown to be effective in identifying individuals with dementia. This test includes a combination of a clock drawing test and a three-item recall, requiring only about 3 minutes to administer—making it well-suited for primary care use. While its diagnostic accuracy may vary depending on geographic region and scoring method, studies consistently report high sensitivity and specificity for detecting cognitive impairment. Research has demonstrated that the clock drawing test alone can reliably distinguish patients with mild neurocognitive disorder (NCD) from cognitively normal older adults, offering strong diagnostic precision. Since episodic memory loss is common in mild NCD, recall-based tests alone may also serve as valuable screening tools, and evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis suggests they outperform the MMSE and MoCA in detecting amnestic forms of mild NCD. The graphical Mini-Cog was developed for rapid cognitive impairment screening in settings where a numerical score (0–5) is not required. Click here to access the Mini-Cog and graphical Mini-Cog assessments tools.

Saint Louis University Mental Status Exam (SLUMS)5

The Mini-Cog is a very brief cognitive screening tool shown to be effective in identifying individuals with dementia. This test includes a combination of a clock drawing test and a three-item recall, requiring only about 3 minutes to administer—making it well-suited for primary care use. While its diagnostic accuracy may vary depending on geographic region and scoring method, studies consistently report high sensitivity and specificity for detecting cognitive impairment. Research has demonstrated that the clock drawing test alone can reliably distinguish patients with mild neurocognitive disorder (NCD) from cognitively normal older adults, offering strong diagnostic precision. Since episodic memory loss is common in mild NCD, recall-based tests alone may also serve as valuable screening tools, and evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis suggests they outperform the MMSE and MoCA in detecting amnestic forms of mild NCD. The graphical Mini-Cog was developed for rapid cognitive impairment screening in settings where a numerical score (0–5) is not required. Click here to access the Mini-Cog and graphical Mini-Cog assessments tools.

Mini Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination (MACE)6

MACE, a shortened version of the Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination-Revised (ACE-R) and ACE-III developed using Mokken scaling analysis. It includes assessments of attention, memory (via a 7-item name and address recall), verbal fluency, clock drawing, and memory recall, with a total score ranging from 0–30, indicating levels from impaired to normal cognition. MACE is quick to administer, simple to score, and well-received by patients. When appropriate cut-off scores are applied, it serves as a sensitive tool for detecting cognitive impairment and effectively ruling out MCI and dementia. Click here to access the MACE assessment tool.

General Practitioner Assessment of Cognition (GPCOG)7

The GPCOG was specifically created for use in primary care settings. It consists of nine cognitive tasks completed by the patient and six informant-based questions that evaluate cognitive changes over time. The entire assessment takes approximately six minutes to complete. Compared to the MMSE, the GPCOG has demonstrated strong sensitivity and specificity in identifying dementia within a typical primary care population and has been validated in multiple languages and settings. Click here to access the GPCOG assessment tool.

Beyond Brief screening tools: Other Assessment Tools for Cognitive Testing

The results from the cognitive screening tests can be useful to indicate the need for a consult with other specialists for further comprehensive examinations. Several validated and emerging methods are available to support diagnosis and monitoring of patients.

Validated Neuropsychological Batteries8

Full cognitive batteries administered by neuropsychologists involve the use of standardized tests to assess various aspects of cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and sometimes academic functioning. These evaluations are highly individualized and typically begin with a thorough review of medical records and a detailed clinical interview, followed by a tailored battery of tests selected based on the referral question and suspected conditions. Tests assess domains, such as memory, attention, language, executive function, and more, and may take from under an hour to several hours depending on the patient and complexity of the case. Performance and symptom validity tests are also used to ensure accurate results, and findings are used to provide a clear diagnosis along with personalized recommendations.

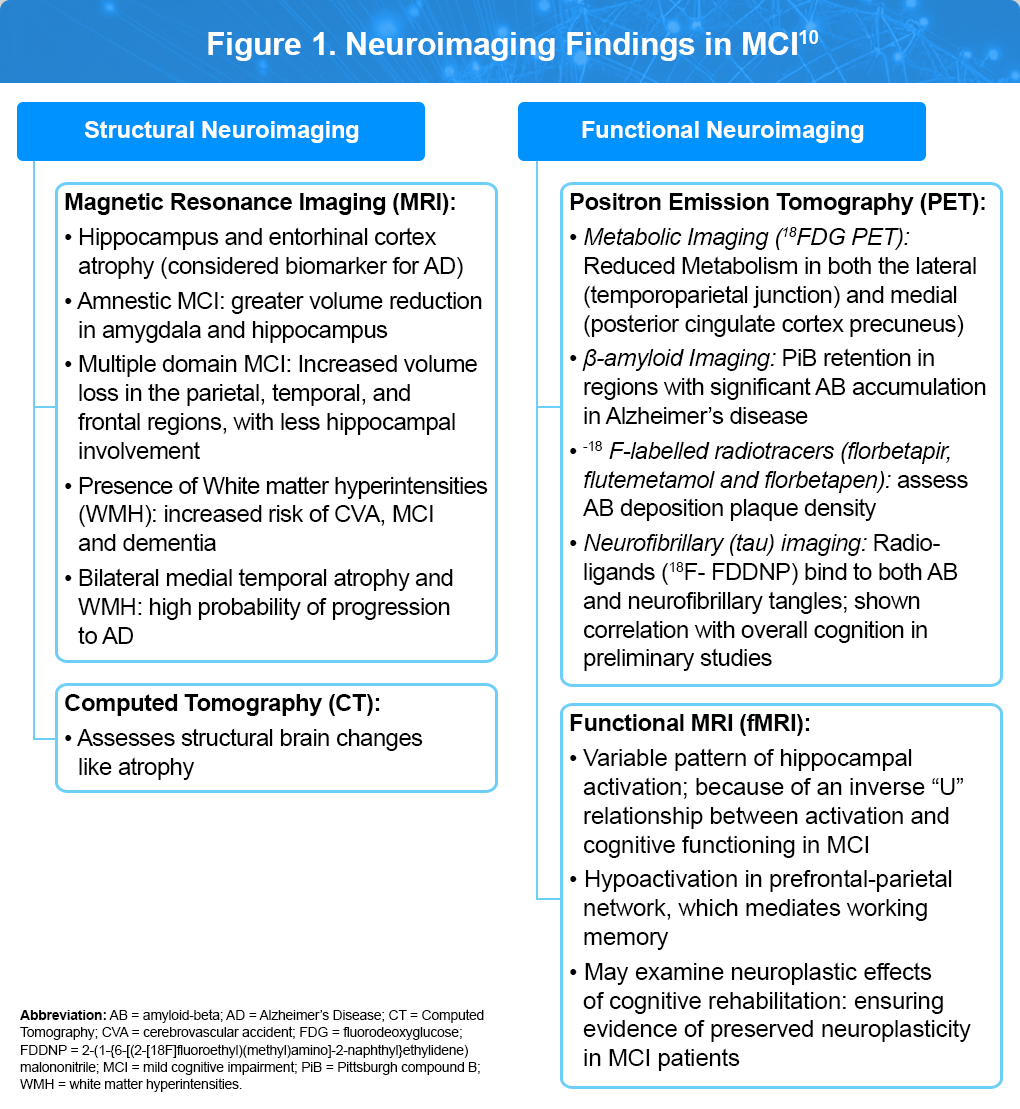

Neuroimaging9,10

As illustrated in Figure 1, Different brain imaging techniques, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT), provides detailed anatomical information, while functional imaging, including functional MRI (fMRI), positron emission tomography (PET), and magnetoencephalography (MEG), allow the examination of the structure, biochemistry, metabolic state, and functional capacity of the brain. All of the major neurodegenerative disorders have relatively specific imaging findings that can be identified. Imaging can also assist in differentiating types of dementia or ruling out reversible causes. The future of utilizing brain imaging for cognitive impairment and dementia will likely involve combinations of imaging techniques to identify the presence of a molecular abnormality, to gauge its impact on the brain structure and function, and to predict and follow the effects of treatment.

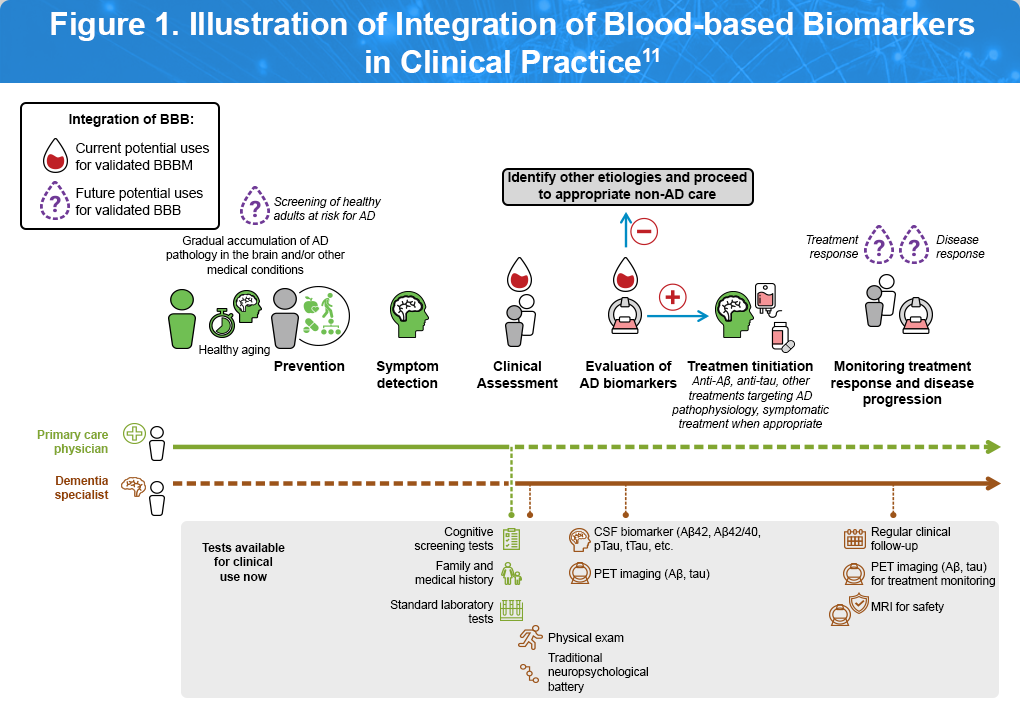

Blood-Based Biomarkers11

Recent advancements have made it possible to detect Alzheimer’s disease pathology, such as, amyloid buildup, tau tangles, and neurodegeneration using simple blood tests. Figure 2 outlines the current and emerging roles of blood-based biomarkers along a patient’s clinical care pathway, beginning with a visit to a primary care physician (indicated by the light green line) or a dementia specialist (brown line). Currently, validated blood-based biomarkers can support the diagnostic process when used alongside clinical evaluation, serving as confirmation of underlying pathology to guide the initiation of approved treatments (represented by the red drop). Looking ahead, as research progresses, these biomarkers may also be used to screen asymptomatic individuals at risk for Alzheimer’s disease, based on age, family history, or comorbidities—and to monitor treatment response and disease progression (purple drop).

Summary

Early detection of cognitive impairment in primary care is essential for improving patient outcomes, enabling timely intervention, and supporting families in care planning. A variety of brief, validated screening tools—such as the MoCA, MMSE, Mini-Cog, SLUMS, M-ACE, and GPCOG—offer clinicians practical options to identify patients who may need further evaluation. While each tool has its strengths and limitations, they are increasingly supported by advanced diagnostics, including blood-based biomarkers and imaging, making early cognitive assessment both feasible and clinically meaningful. Routine integration of these strategies can help reduce diagnostic delays and improve long-term care for individuals at risk of dementia.

References

- Atri A, Dickerson BC, Clevenger C, et al. The Alzheimer’s Association clinical practice guideline for the diagnostic evaluation, testing, counseling, and disclosure of suspected Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders (DETeCD-ADRD): Validated clinical assessment instruments. Alzheimers Dement. 2025;21:e14335.

- Wood JL, Weintraub S, Coventry C, et al.. Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) Performance and Domain-Specific Index Scores in Amnestic Versus Aphasic Dementia. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2020;26:927-931.

- Arevalo-Rodriguez I, Smailagic N, Roqué I Figuls M, Ciapponi A, Sanchez-Perez E, Giannakou A, Pedraza OL, Bonfill Cosp X, Cullum S. Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) for the detection of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias in people with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015:CD010783.

- Limpawattana P, Manjavong M. The Mini-Cog, Clock Drawing Test, and Three-Item Recall Test: Rapid Cognitive Screening Tools with Comparable Performance in Detecting Mild NCD in Older Patients. Geriatrics (Basel). 2021;6:91.

- Howland M, Tatsuoka C, Smyth KA, Sajatovic M. Detecting change over time: A comparison of the SLUMS examination and the MMSE in older adults at risk for cognitive decline. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2016;22:413-419.

- Larner AJ. MACE for Diagnosis of dementia and MCI: Examining cut-offs and predictive values. Diagnostics (Basel). 2019;9:51.

- Sheehan B. Assessment scales in dementia. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2012;5:349-358.

- Schaefer LA, Thakur T, Meager MR. Neuropsychological assessment. StatPearls Last Updated May 16, 2023. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513310/

- Tartaglia MC, Rosen HJ, Miller BL. Neuroimaging in dementia. Neurotherapeutics. 2011;8:82-92.

- Subramanyam AA, Singh S, Raut NB. Clinical practice guidelines for assessment and management of mild neurocognitive disorder. Indian J Psychiatry. 2025;67:21-40. Erratum in: Indian J Psychiatry. 2025;67:280.

- Hampel H, Hu Y, Cummings J, et al.Blood-based biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease: Current state and future use in a transformed global healthcare landscape Neuro. 2023;111:2781-2799.

Accessed on September 22, 2025.